The single thing I can think about is escape. How to escape from here, and go back to my mountain and be free again, full of joy, full of life. Yet, there are no keys to this prison, not even doors leading in or out of my cell. Just walls, impenetrable granite walls with a small window in one corner, through which the food is being served, the air circulates and the images of the joys of freedom of the outside world come in to visit me through the cable and the Internet: the images that torment me every day, but my existence would be even more lonely and desperate without them.

Dreams are the only way out. Dreaming of what would I be doing if I was not here. Dreaming of what would I do if, not if, but once I get out of here. Planning my days. Scheming the adventures. Enjoying the virtual movements that I was able to memorize once I was able to perform them, like running and swimming and snowboarding and working out, and warming up my mind for the day I shall be able to do them again.

It is, perhaps, true that those who come to prison for their first time, suffer the most: they are not yet aware of the immense pleasure of release and return to their free selves. And I am a repeat offender. Iíve been here many times. And I always got out so far. And there is still a tiny voice in the back of my head saying that this time I will get out again. Although, with idle days passing, I withdrew myself more and more away from the little window, and the dreams became less saturated in color and light.

I have friends who view situations like this as an opportunity to learn, and accept and adapt to their new realities more stoically, and I have friends who are angry and desperate over their doom seeking justice, redemption, satisfaction for the cruel act of fate, asking: "Why me?" But of course, there were many others who had been there before me and there were many others who had it worse than me, too. And the despair and anger are not going to bring the healing any quicker than the stoicism. Still, I find it very difficult to accept accidents for what they are: a statistically probable event in an extreme sport. Particularly when they happen to me. I guess, this is natural. Retracing the actions that lead to the injury helps rationalize and understand the reasons, but does not help understand the answer to the question: "why me?"

Because - how would anyone understand that answer? I just came back from a long trip to Europe. I havenít rode for about two weeks. This was my first day back to Vermont in what probably was the best winter in the past two decades. The snow at the top of K1 gondola was topping the wooden fence on the way to the peak lodge. Iíve never seen this before. The snow was everywhere and it was simply too beautiful. I was able to, for a moment, take my mind off from the technical problems Iíve been experiencing with my computer, from all the hectic, stressful stuff I was subjected to both on my trip over Europe and back with various business in New York city, and I was happy, genuinely happy, riding hard with my friends.

And then it happened. There is no doubt that I made a judgement mistake - after all, most of the accidents are due to the human error, and most of the human errors are simple misjudgements: there was a drop, that due to the heavy snowfall, was caved in with snow. In theory one could ride the cavity, provided that he lifts the tip of his board before the extremely steep concave drop becomes the flat slope. But this happens so quickly, since the steep area is relatively short, and the transition in the flat light is nearly un-palpable. Therefore, to ride it instead of dropping it, would be very impractical. And I donít understand why I did it. But the expected happened: I couldnít see the transition, I didnít lift my tip up in time, I caught snow with it, tripped over, flew over my imaginary handlebars and fell. The unmitigable, passionless laws of physics were satisfied to the letter.

And then it happened. There is no doubt that I made a judgement mistake - after all, most of the accidents are due to the human error, and most of the human errors are simple misjudgements: there was a drop, that due to the heavy snowfall, was caved in with snow. In theory one could ride the cavity, provided that he lifts the tip of his board before the extremely steep concave drop becomes the flat slope. But this happens so quickly, since the steep area is relatively short, and the transition in the flat light is nearly un-palpable. Therefore, to ride it instead of dropping it, would be very impractical. And I donít understand why I did it. But the expected happened: I couldnít see the transition, I didnít lift my tip up in time, I caught snow with it, tripped over, flew over my imaginary handlebars and fell. The unmitigable, passionless laws of physics were satisfied to the letter.

The tree that I never remembered as being there before, perhaps because I went un-naturally far to the left that time, just materialized in my path - I saw it coming - it was a rather small tree, looking thin and pliant, so I tackled it with a degree of confidence - but I hit it right at the bottom, close to the ground, where trees are as hard as rocks, and I heard a cracking, snapping sound, which, as I realized when I stood up, did not come from the tree. It came from inside me. Something inside my left shoulder area gave in. I instantly felt different. I felt something was very wrong that time. And that was even before I had to start supporting firmly my left elbow with my right hand to prevent the immensely sharp pain - on the verge of losing consciousness - to spread from the sharp ends of the broken clavicle swimming and poking around in the soft tissue.

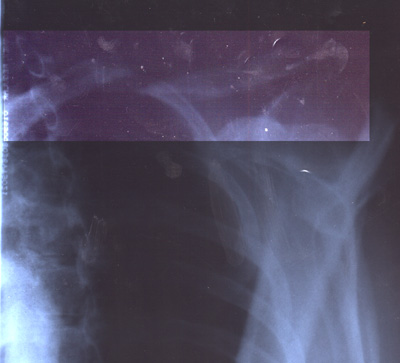

So, I told Tony and Alex that I would not be able to ride to the bottom with them, and they got ski patrol over, and while we were waiting for the sled, Tony virtually took the tree that hurt me out of the ground, so it would not hurt anybody else, and then the sled came, and by the time the sled brought me to the Killington Base Lodge, the ambulance car came and took me to the Rutland Regional Medical Center, where the X-rays were taken, confirming the obvious. I was quite surprised with the methods that modern medicine uses to heal the clavicle fracture: the sling and the strap are perhaps not much different than they were five thousands years ago. Ok, the caveman perhaps did not have the same materials available, and he probably did not understand what was going on with him, but the methods were not different: immobilize and wait until the pain goes away.

Three weeks and counting, and I am still waiting. I can let my left arm now dangle on the side, even hold and curl a five-pounder, but any movement that involves the pectoral or the front deltoid muscle, is still impossible to perform. It is weird how structurally debilitating this injury is: the other shoulder and elbow hurt from their own fallacies and because now they have to do all the work, the back hurts from lying down on it all the time, the upper body muscles atrophy and the adipose tissue deposits itself on all the predictable places, changing my shadow on the wall to an undesirable shape. It is true what doctors said - that this is an annoyance break. It is a small bone. And the whole left side of my upper body is virtually paralyzed due to its injury. How to dress myself? Prepare a meal? Take a shower?

Ryan, who had the same injury last season, came to see me, with his girlfriend (and she went through this with him, like Indira is going through this with me right now), before I left Vermont, and they didnít have any pretensions that they could really cheer me up: it sucks, and it sucks for weeks, for a couple of months actually, and there is nothing anybody can do about it, but then, eventually, it goes away, and with time, the bad memories of it vane. But the time is what I donít feel like having in abundance. The body-intensive life is very short - maybe about 30 years if not less - and I am already in the last third of it, so I feel like every minute of physical joy counts. And there are so many things that I want to do. Like this year, because of injury, I missed riding the whole April, I missed the best conditions Iíve ever seen, I missed the trip to Tuckermanís Ravine, that I wanted to do this Spring, I missed participating at the AASI exam at Sunday River and in general I rode just 78 days this season - of 100 that I wanted to ride at least.

In those days that I rode I learned to be more confident spinning front-side 180-s, dropping from natural objects (maybe too confident with that one), jumping over man-made obstacles and riding trees, which became my favorite snowboarding "discipline." This amounts to maybe a third of what I wanted to accomplish this season, which makes me quite sad. I guess trees were my hide-out always. I mean - I liked to go into the trees from my very first year at Killington, when Pat took me into the glades between Header and Swirl and disappeared before I managed to recover from my first wipe-out. I admit: in the beginning it was easier for me to bear my sucking on the snowboard, when only speechless birches bore witness. And by doing it over and over again, I eventually stopped sucking. Maybe if I spent as much time in the half-pipe as much Iíve spent in the trees, I would not suck in the pipe, either.

My standards changed with years at Killington. On my first year, I was essentially happy to be able to get down the formidable, treacherous trails in one piece, following my friends. Now, I want to ride faster, more aggressive, attempt tricks and add style. My injuries followed that change of pace: I am way past slow speeds and flat terrain at which beginners endure wrist injuries. And I am not yet, and perhaps I will never be, in the high speed, big air, multiple rotations zone of skull crushing, spine snapping, life ending injuries. I am in that half-way area of broken ribs, fractured collarbones and dislocated shoulders. And, of course, I will be back.